Five Landscape Paintings

In this short post I’m looking at landscape painting, specifically a small selection of traditional landscape paintings. The subject of landscape painting has a long history up to the present and all approaches are important.

I’m interested in one idea here — the feeling that comes from viewing a good painting when looking at it. I’m curious about the relationship between that experience and how a painting is made. I need to point out though — I don’t think about this while I’m actually painting! Nevertheless I find this idea fascinating.

When I look at a painting such as John Kensett’s, Eaton’s Neck Long Island (below), I feel a contrast between the simplicity of the painting and the feeling I experience when viewing it. It’s so simply composed it’s almost a painting about nothing, A spit of land coming out onto the water of the Long Island sound, water, sky and on the horizon dots of paint for boats and land off in the distance. That’s it. And yet this has a powerful feeling to it.

The question is how does the artist get there, to that feeling in the painting? What is it in the painting that produces that feeling when I look at it? It’s like experiencing something like a narrative that comes from behind the actual subject; not a literal story about the subject but it’s something else that happens because of the subject matter and the paint and the process.

The viewer needs to bring something to the painting and the artist needs to bring something to the viewer; it’s a 50-50 relationship.

Look at this painting by Martin Johnson Heade, York Harbor Maine (below), 1877. This painting definitely has a feeling to it, a mood, an atmosphere. The artist saw that and he saw it in front of him in nature and he knew how to take that information and bring that paint application and color to make a painting that is clearly entering into sublime territory. This artist also is part of the Hudson River school of painting where luminosity and the sublime were important for getting their message across. As a viewer I don't think it's too difficult to connect with what's going on in this painting, the artist makes it easily accessible to us…this bright, glowing sun on a hazy day, the softness of the air in the atmosphere can be felt, the stillness of the water with the boats and reflections, we travel the distance from the rocky foreground to the fading tree line in the distance.

A “conversation” with an artwork starts when I bring my life experiences to the work. I may empathize with the subject. For example, I know what it feels like to be in a beautiful landscape, and I can recognize that in a painting and then start to experience that narrative of feelings. In this Dutch painting by Van Ruisdael, Wheat Field (below), I was swept away into that space when I viewed it in person at a museum. However it goes beyond the obvious perspective in the painting, but then there is more the artist also brings to it.

This is what I teach to; in the seeing and sensitivities in landscape painting, and what is literally out there in the real world that waits for us and informs us to be better painters. I teach to these things and bring them to the attention of my students.

In my most inspired conversations about art these are things I love to talk about, this exploration and exchange of ideas, delving into what is happening and how and why it is important. And when I teach I pinpoint the essential skills students need to create successful paintings.

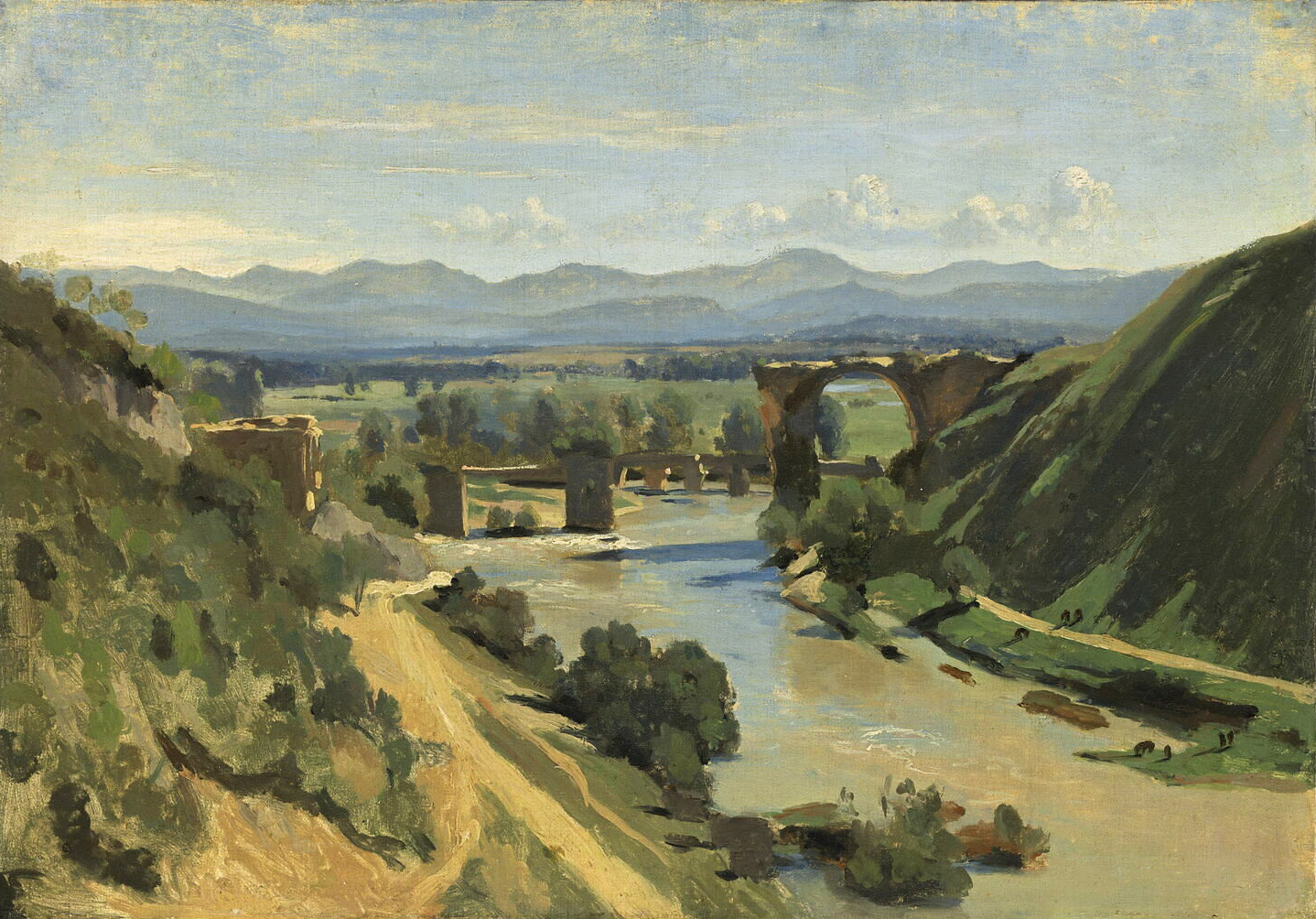

Coming up are two additional paintings here for you to enjoy. The first one is by the French artist Corot, the Bridge at Narni, showing a river and the remains of a bridge.

The second painting is by the French pointillist painter Seurat, Bridge at Courbevoie.